March on Washington - 1963

The World Hears of Dr. King's "Dream

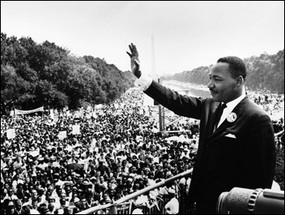

The 1963 March on Washington attracted an estimated 250,000 people for a peaceful demonstration to promote Civil Rights and economic equality for African Americans. Participants walked down Constitution and Independence avenues, then — 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed — gathered before the Lincoln Monument for speeches, songs, and prayer. Televised live to an audience of millions, the march provided dramatic moments, most memorably the Dr. King’s Martin Luther King Jr. "I Have a Dream" speech.

Far larger than previous demonstrations for any cause, the march had an obvious impact, both on the passage of civil rights legislation and on nationwide public opinion. It proved the power of mass appeal and inspired imitators in the antiwar, feminist, and environmental movements. But the March on Washington in 1963 was more complex than the iconic images most Americans remember it for. As the high point of the Civil Rights Movement, the march — and the integrationist, nonviolent, liberal form of protest it stood for — was followed by more radical, militant, and race-conscious approaches.

The march was initiated by A. Philip Randolph, Asa Philip Randolph International President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, President of the Negro American Labor Council, and Vice President of the AFL-CIO. Other organizers and co-sponsors were: Bayard Rustin, Whitney Young of the Urban League, SNCC’s John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, and CORE’s James Farmer who began planning for the march during the summer of 1963. They decided that the march would be in support of jobs, freedom, and President John F. Kennedy’scivil rights legislation. The march was planned for August 28, 1963. Bayard Rustin, a close associate of Randolph's and organizer of the first Freedom Ride in 1947, orchestrated and administered the details of the march.

Planning for the event was complicated by differences among members. While Randolph (and the National Urban League's Young) focused on jobs, the other groups were focused the continued fight for freedom. Both SNCC and CORE were organizing nonviolent protests against Jim Crow segregation and discrimination. In 1963 King's SCLC was waging a long campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama. The violence Sheriff Bull Connor and his men visited upon peaceful demonstrators in Birmingham brought national attention to the issue of civil rights. As Rustin later said, credit for mobilizing the March on Washington could go to "Bull Connor, his police dogs, and his fire hoses."

Operating out of a tiny office in Harlem, Rustin and his staff had only two months to plan a massive mobilization. Money was raised by the sale of buttons for the march at 25 cents apiece, and thousands of people sent in small cash contributions. The staff tackled the difficult logistics of transportation, publicity, and the marchers' health and safety. Attention to detail was crucial, for the planners believed that anything other than a peaceful, well-organized demonstration would damage the cause for which they would march.

On August 28 the marchers arrived. By 11 o'clock in the morning, more than 200,000 had gathered by the Washington Monument, where the march was to begin. It was a diverse crowd: black and white, rich and poor, young and old, Hollywood stars and everyday people. Despite the fears that had prompted extraordinary precautions (including pre-signed executive orders authorizing military intervention in the case of rioting), those assembled marched peacefully.

The speech written by CORE's James Farmer, imprisoned in Louisiana, was read by Floyd McKissick. Farmer said the fight for legal and economic equality would not stop "until the dogs stop biting us in the South and the rats stop biting us in the North." King, the last speaker of the day, stirred the audience and built to his reportedly extemporaneous "I have a dream" finale. The march ended at 4:20 in the afternoon, ten minutes ahead of schedule. The organizers then met with President Kennedy.

The March on Washington was a success. It had been powerful, yet peaceful and orderly beyond anyone's expectations. It was, according to most historians, the high tide of that phase of the Civil Rights Movement.

Far larger than previous demonstrations for any cause, the march had an obvious impact, both on the passage of civil rights legislation and on nationwide public opinion. It proved the power of mass appeal and inspired imitators in the antiwar, feminist, and environmental movements. But the March on Washington in 1963 was more complex than the iconic images most Americans remember it for. As the high point of the Civil Rights Movement, the march — and the integrationist, nonviolent, liberal form of protest it stood for — was followed by more radical, militant, and race-conscious approaches.

The march was initiated by A. Philip Randolph, Asa Philip Randolph International President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, President of the Negro American Labor Council, and Vice President of the AFL-CIO. Other organizers and co-sponsors were: Bayard Rustin, Whitney Young of the Urban League, SNCC’s John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, and CORE’s James Farmer who began planning for the march during the summer of 1963. They decided that the march would be in support of jobs, freedom, and President John F. Kennedy’scivil rights legislation. The march was planned for August 28, 1963. Bayard Rustin, a close associate of Randolph's and organizer of the first Freedom Ride in 1947, orchestrated and administered the details of the march.

Planning for the event was complicated by differences among members. While Randolph (and the National Urban League's Young) focused on jobs, the other groups were focused the continued fight for freedom. Both SNCC and CORE were organizing nonviolent protests against Jim Crow segregation and discrimination. In 1963 King's SCLC was waging a long campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama. The violence Sheriff Bull Connor and his men visited upon peaceful demonstrators in Birmingham brought national attention to the issue of civil rights. As Rustin later said, credit for mobilizing the March on Washington could go to "Bull Connor, his police dogs, and his fire hoses."

Operating out of a tiny office in Harlem, Rustin and his staff had only two months to plan a massive mobilization. Money was raised by the sale of buttons for the march at 25 cents apiece, and thousands of people sent in small cash contributions. The staff tackled the difficult logistics of transportation, publicity, and the marchers' health and safety. Attention to detail was crucial, for the planners believed that anything other than a peaceful, well-organized demonstration would damage the cause for which they would march.

On August 28 the marchers arrived. By 11 o'clock in the morning, more than 200,000 had gathered by the Washington Monument, where the march was to begin. It was a diverse crowd: black and white, rich and poor, young and old, Hollywood stars and everyday people. Despite the fears that had prompted extraordinary precautions (including pre-signed executive orders authorizing military intervention in the case of rioting), those assembled marched peacefully.

The speech written by CORE's James Farmer, imprisoned in Louisiana, was read by Floyd McKissick. Farmer said the fight for legal and economic equality would not stop "until the dogs stop biting us in the South and the rats stop biting us in the North." King, the last speaker of the day, stirred the audience and built to his reportedly extemporaneous "I have a dream" finale. The march ended at 4:20 in the afternoon, ten minutes ahead of schedule. The organizers then met with President Kennedy.

The March on Washington was a success. It had been powerful, yet peaceful and orderly beyond anyone's expectations. It was, according to most historians, the high tide of that phase of the Civil Rights Movement.