Montgomery Bus Boycott

The End of Discrimination on Public Buses in the South

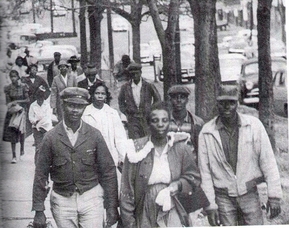

In December of 1955, 42,000 black residents of Montgomery began a year-long boycott of city buses to protest racially segregated seating. After 381 days of taking taxis, carpooling, and walking the hostile streets of Montgomery, African Americans eventually won their fight to desegregate seating on public buses, not only in Montgomery, but throughout the United States.

The protest was first organized by the Women's Political Council as a one-day boycott to coincide with the trial of Rosa Parks, who had been arrested on December 2, 1955, for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a segregated Montgomery bus. By the next morning, the Council, led by JoAnn Robinson, had printed 52,000 fliers asking Montgomery blacks to stay off public buses on December 5, the day of the trial. Meanwhile, labor activist E.D. Nixon, who had bailed Parks out of jail, notified Ralph Abernathy, minister of the First Baptist Church, and Martin Luther King Jr., the new minister at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, of Parks' arrest. A group of about 50 black leaders and one white minister, Robert Graetz, gathered in the basement of King's church to endorse the boycott and begin planning a massive rally for the evening of the trial.

On the morning of Parks' trial, buses rumbled nearly empty through the streets of Montgomery. Police officers with shotguns roamed in search of imaginary "Negro goon squads" whom they believed were forcing blacks to stay off the buses.

After Parks lost her case and was convicted of violating the segregated seating laws, black leaders met again to organize an extension of the bus boycott. To this end, they formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), and elected King as its president. That evening, 7000 blacks crowded into Holt Street Baptist Church, where King addressed and inspired the audience with his words: "There comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression." Even as the protesters and black leaders were confronted with escalating violence, they maintained both nonviolent resistance and their exhausting day-to-day schedule without public transportation. In June, a federal court ruled segregated seating unconstitutional, and the case went on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court under the case name Browder v. Gayle. (also see Claudette Colvin)

The Montgomery Bus Boycott had implications that reached far beyond the desegregation of public buses. The protest propelled the Civil Rights Movement into national consciousness and Martin Luther King Jr. into the public eye.

The protest was first organized by the Women's Political Council as a one-day boycott to coincide with the trial of Rosa Parks, who had been arrested on December 2, 1955, for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a segregated Montgomery bus. By the next morning, the Council, led by JoAnn Robinson, had printed 52,000 fliers asking Montgomery blacks to stay off public buses on December 5, the day of the trial. Meanwhile, labor activist E.D. Nixon, who had bailed Parks out of jail, notified Ralph Abernathy, minister of the First Baptist Church, and Martin Luther King Jr., the new minister at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, of Parks' arrest. A group of about 50 black leaders and one white minister, Robert Graetz, gathered in the basement of King's church to endorse the boycott and begin planning a massive rally for the evening of the trial.

On the morning of Parks' trial, buses rumbled nearly empty through the streets of Montgomery. Police officers with shotguns roamed in search of imaginary "Negro goon squads" whom they believed were forcing blacks to stay off the buses.

After Parks lost her case and was convicted of violating the segregated seating laws, black leaders met again to organize an extension of the bus boycott. To this end, they formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), and elected King as its president. That evening, 7000 blacks crowded into Holt Street Baptist Church, where King addressed and inspired the audience with his words: "There comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression." Even as the protesters and black leaders were confronted with escalating violence, they maintained both nonviolent resistance and their exhausting day-to-day schedule without public transportation. In June, a federal court ruled segregated seating unconstitutional, and the case went on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court under the case name Browder v. Gayle. (also see Claudette Colvin)

The Montgomery Bus Boycott had implications that reached far beyond the desegregation of public buses. The protest propelled the Civil Rights Movement into national consciousness and Martin Luther King Jr. into the public eye.